Chapter 10: Egypt, 1939-1941

There is much to be said for life in the Services, where one is uprooted from a familiar task every two or three years and sent to some new place where different challenges and experiences will help to develop flexibility, new skills and the ability to adapt to the unexpected, something which will be particularly valuable in time of war. Billeted for the night at the Continental Savoy Hotel, Cairo, Wilfred and I met some half dozen old friends or acquaintances. Another military advantage is that the Army itself and one’s own Regiment or Corps provide an immense club which is quick to welcome tribal newcomers wherever they may travel.

Wilfred and I were naturally anxious to learn what the future had in store for us on this occasion and reported as ordered to Chief Signal Officer Colonel Micky Miller the next day.

The various signposts in life are hidden, more often than not, until well after they have been passed, only to be recognised later in life. One such was waiting for us here. We were asked if either of us had any experience as a Signalmaster. I mentioned my minimal employment of this kind in Catterick and this decided our fates. Wilfred was sent to Palestine, as it was then called, and I was to join Egypt Command Signals.

Any hope I might have had of joining a unit with the standard task of serving a Divisional or Corps Commander evaporated. If any unit deserved the title ‘unique’, this was it. It had looked after communications over the whole country except for those specific to Divisions within Egypt. Our HQ and one Company were Cairo-based. We had another Company in Ismailia in the Canal Zone, a hundred miles to the east. This in turn provided facilities in Port Said and Suez, fifty miles away in opposite directions. There was a third Company in Alexandria, a hundred and fifty miles to the west with a Brigade Section reporting direct to Cairo a hundred and twenty miles further still along the coast. Though I never met them there were also detachments 600 miles to the south at Wadi Halfa on the Sudanese border and 400 miles to the west of Cairo at the Libyan frontier at Solum.

I was directed to Cairo Area Signals, providing communications for the ever-expanding HQ British Troops in Egypt, known as BTE, which was in overall operational control until General Wavell’s GHQ Middle East was developed.

Our unit took on more responsibilities from time to time until it became unmanageable and parts of it were hived off to form separate units in their own right. Other peculiarities of our unit were to develop and will appear later in the story. For the time being I moved to Abbassia a few miles to the north which was a small military town of some antiquity. If its name stems from the Egyptian reign of Pasha Abbas it would date to the 1850s. Abbas it was who had come to power at a time when the centuries-old tie binding of his country to Turkey was weakening. In Abbassia fine stone-built housing of his time had been extended by many wooden huts. It housed several British units on the edge of the desert. There was also an important and substantial fenced-in area named ‘Polygon’ with tall aerial masts and the primitive equipment that provided our wireless link with the United Kingdom.

Instant gardening in Cairo’s circumstances is easy. A suitable trench is dug and a few loads of Nile mud ordered. The garden then flourishes within weeks.

Cairo Area Signals had an office in a hutted area at the desert edge that included the Sergeants’ Mess, a small bore rifle range and a pigeonnaire. Perhaps the concept was that pigeons could be given to units going to the Desert War so that they could send back messages to tell us how they were getting on. It is a pity that this form of communication lapsed if only because the ‘fanciers’ who commanded these flocks of birds were inevitably great characters such as any unit would be proud to possess.

Then there was Corporal Bottomley who approached me to talk about Motor Cycling. He had won the Egyptian trials and wondered if I would like to tour some of their course with him. I passed muster and this led to immediate acceptance by the soldiery as someone worth having.

Captain Harold Winterbotham was my Company Commander and our parish included a myriad collection of military telephone exchanges in the extended Cairo area and a lesser number of Signal Offices for message handling. For ease of access to their work a large proportion of our men were accommodated in the Kasr el Nil barracks in central Cairo close to BTE Headquarters, where they worked, and remote from us except when we visited their signal centre.

Apart from controlling and improving communications we had responsibilities which would never be given to any unit today. Harold and I were deputed to be the officers for liaison between the Army in Egypt and the Egyptian State Telephone and Telegraphs. This had the merit that we worked with and got to know several of the planning and executive engineers of the EST. Opportunities for meeting and making friends with Egyptians were few, which was a pity. Requirements for new facilities such as an Ordnance Depot in the Canal Zone or for the New Zealand Division at Maadi and many others came our way and I would be sent off with an EST representative to view the site and discuss the requirements planned. At one time when Harold was carried off to hospital the whole of this important responsibility passed to me, a Royal Signals officer with three years service.

There were delays, as much of the equipment had to be ordered from overseas.

The greatest time of complaint was the Muslim month of Ramadan with dawn to dusk fasting for all Muslims. We became the buffer between unhappy users waiting for communications and labourers carrying out at least some work whilst following the dictates of their religion. One forceful complaint that I had to deal with came from Lt Colonel Mutt Mathew who commanded 7th Armoured Divisional Signals. I feared that I was in disgrace, but shortly afterwards a message from this officer was passed to me that if I applied to join his unit, he would be very glad to have me. Although this was another clear signpost I did not feel that it was a personal choice. I was already very busy with something important, so I did not apply. It was many months before professional engineers from the UK Post Office arrived as uniformed officers and took over our tasks as staff officers operating at HQ BTE.

Egypt had always had an excellent reputation as an overseas station with a pleasant healthy climate and rainfall in Cairo averaging a little over an inch a year. Facilities for sport were excellent and a very civilised way of life was there for the taking. Perhaps it was too civilised for developing some of the tougher aspects of military service. With its Turkish overlords and local leaders too concerned with claiming the good things in life for themselves and their cronies, the nineteenth century had not been a happy one for Egyptians. The French and British had been active in the creation of the Suez Canal, which was opened in 1869, and difficulties arose over its management. In 1881 Ahmed Arabi, an army officer from the ranks, led an uprising against the Turkish and European oppressors, which complicated matters further. He was defeated in the battle of Tel-el-Kebir by British intervention under Sir Garnet Wolsey. Arabi was tried, found guilty and banished to Ceylon.

In 1884 a British Consul General was appointed under the guidance that:

‘Egypt must be governed in a truly liberal spirit; its task being the duty of giving advice with the object of ensuring that the order of things to be established should be of a satisfactory character and possess the elements of stability and progress.’

Thus it came about that Egypt was governed by the British from 1884 to 1922.

In 1885 Major General Sir Evelyn Wood VC was to raise an army of 8000 from the Egyptian fellahin, the peasant farmers. Lieutenant Kitchener RE was one of his officers. It was presumably from this start that the Egyptian Army was built and was still served by a British Military Mission in 1939.

There were family connections with these activities. My Great Uncle Kenneth Baynes served with the 79th, the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders as Adjutant at Tel-el-Kebir. In 1884-5 he served in the Sudan. Like many of his time he retired on getting married. His brother Gilbert of the 60th Rifles was a staff officer during the Nile Expedition. Kitchener deserves further mention too. Even the greatest of men have mothers and his, Frances Chevallier, was a relation of my Cazenove grandmother. Herbert Kitchener’s association with Egypt and the Sudan was to be a lengthy one culminating when he was Governor for the period 1911-14.

Willie Baynes, of my mother’s generation, was a judge in Cairo on the outbreak of the Great War. He resigned at the age of forty to become a platoon commander in France with the Coldstream Guards. Severely wounded, he won the Military Cross and lived on to the great old age of ninety-five.

Gradually I was getting to know Cairo and its surroundings. Both British and French influences had been strong and families of many nations had moved there and remained involved in trade, cotton, the Canal management, the Universities and the Police. Driving to BTE of a morning I would pass strings of polo ponies being trotted to the Gezira Club. The Opera House had closed but there were concerts to go to and evening entertainment prospered at clubs and restaurants, as did other pursuits at organisations of varying repute. Avenues were lined with decorative flowering trees and the central areas were well laid out with fine buildings. Flies were tiresome everywhere and flywhisks, coloured ponytails with convenient handles, became part of uniform. A 1989 visit showed me that flies had been defeated - a great improvement.

Having visited Egypt after a gap of 50 years I can see the difficulty of providing any picture of the place we lived in when first I was there. At the time I arrived the population of the city was assessed at just over one million. For us there was a five-mile drive over open desert from the Cairo zoo on the outskirts of the city to the Pyramids at Mena. Now the impression is of a city largely populated by Egyptians, with constant traffic snarl and a fair sprinkling of tourists. On a visit to the Pyramids care is needed in taking photographs to avoid a background of buildings instead of wide open desert space.

Today Cairo’s population is over six million and if one includes the extended peripheral built-up areas that we might call greater Cairo the figure reaches thirteen million. The populations of Britain and Egypt are similar and Egypt has four times the land area, though only one fiftieth of this is productive.

In summary we knew a stylish cosmopolitan city such as that which attracted Edwardian visitors to a pleasant, healthy and interesting country. My FitzGerald uncle spent two months there in 1911 as Chaplain to Bishop Ryle who received medical treatment at Helouan, with the natural sulphurous smelling baths of the German clinic. They returned to participate in the Coronation of King George V. The cure was not entirely a success. My uncle notes as the Bishop’s biographer that

‘He certainly needed somebody by him, for the ceremony was long and exhausting, and during its course I was obliged to dose him twice with sal-volatile and once with brandy and water.’

I have yet to mention a surprise I encountered immediately on arrival in Cairo. I found that Ralph Bagnold was there and not far away in the East Africa to which he had been posted. I dined with him and learned his tale. There had been delays when his ship reached Port Said and he set off to visit Cairo where the newspapers were quick to report his arrival and congratulate the War Office on their wisdom in sending an expert on this country to the right place. This information was passed to General Wavell who was in Cairo, incognito, preparing for the announcement of his appointment as Commander in Chief, Middle East. He sent for Bagnold and suggested that he would be much more useful in the country he knew well rather than one he had never visited. Ralph Bagnold entirely agreed and the change in posting was made, resulting in due course in the major and original contribution Bagnold made, not only to Desert Warfare but also to the overall use of Special Forces.

Over the next year the breadth of my interests were widening through guidance and adventurous expeditions arising from the Bagnold link. I was told that the Cairo Museum was worth a visit on a particular Sunday as Lucas, important in the exploration of Tutenkhamen’s tomb, would be there. This I did and following him round learned something of the detective work he carried out as a chemist. A wooden device found collapsed in a tomb would have brown markings which, when tested, turned out to have been leather ties. A three dimensional jig saw puzzle could then be carried out to establish the purpose of the item. Lucas was rather scathing about the jewellery of 1500 BC saying that it had been much better a thousand or more years earlier. Sadly the Museum closed shortly after this visit.

Censorship of soldier’s mail was a laborious task. The only memorable missive I handled was a weighty one given me by my mentor, Bagnold. It was headed ‘Beach Formation by Waves’ and was full of the mathematics and physics needed to support his conclusions. I like to believe that this paper was the one that led Bagnold, the author, to becoming a Fellow of the Royal Society. By some mischance he was not told of this distinction and only learned about it when he returned to England in 1944.

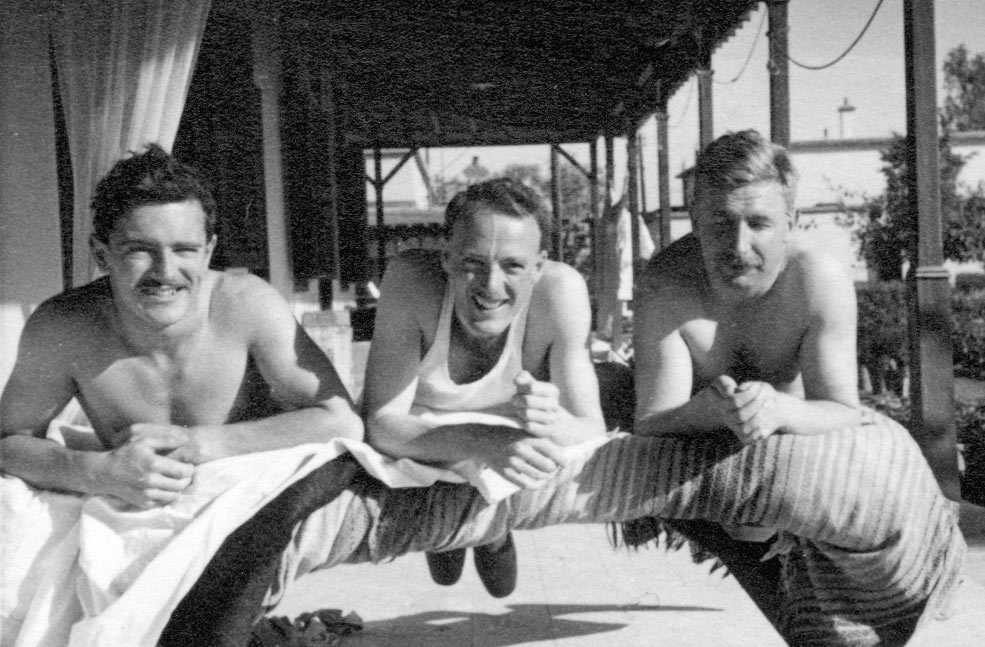

Bagnold invited a number of us to go rock climbing in the area of the Tura caves that had provided the stone for the building of the Mena Pyramids five thousand years before. We used the area several times, passing on the way there a petrified forest, 50 million-year old fossilised remnants of trees. How Bagnold discovered interested people for such pursuits I do not know. As well as Harold Winterbotham and myself from Signals there were a Sapper, Boomer Heath and Digby Raeburn from the Scots Guards, a name I knew in the skiing world. He and I were to work together in later years on Army and National skiing committees and in the Alps.

The year 1940 was seen in with a hectic weekend. Ralph Bagnold planned a visit to several of the pyramids to the south of the well-known ones and then on to the Fayyum, the most important of the Egyptian oases. It lies sixty miles to the south of Cairo, measures some forty miles across and is fed with water by ‘Joseph’s Canal’ from the River Nile. At its lowest point it is 150 feet below sea level and there the substantial Lake Qarun is formed. Shades of earlier times were recalled when we stayed at the Hôtel du Lac, run by an Austrian. With a population of a million, extraordinary fertility and occupation recorded for six millennia it is an area of considerable agricultural importance. As well as seeing the main town and the ancient water wheels we set off westward into the desert where I received sun compass instruction. Good navigation in the desert is of extreme importance if any considerable distance is to be travelled. We used a Bagnold-designed compass. Reaching the Wadi Rayan whole areas of the desert shone brightly, the sun being reflected by thousands of flat round fossils the size of large coins.

Further to the west lies the Qattara Depression, somewhat deeper and ten times the size. With no fresh water supply it is full of salt marshes. The steep fissured rock walls to its north, with the sea beyond, provide the gap of El Alamein, making this the vital defensive platform without an open flank where resistance could hold until the great turning point battle was fought there.

Our way out from Cairo had taken us to the step-sided Midoum Pyramid and on the way back we came to the Dahshur group, the tallest of which we climbed and then sought its entrance. I will describe what followed so that others can savour the experience without having to experience it. First we had to wriggle through some twenty feet of a tunnel of uneven stone where breathing had to be achieved without expansion of one’s chest. This opened up into an architecturally fine chamber of considerable height. A second similar though shorter tunnel led to another chamber, similar except for the more powerful aroma of inhabiting bats. The release of tension on reaching fresh air was the most enjoyable part of the whole proceedings.

Returning to Cairo there was a quick change before I joined two friends for an overnight railway trip to Luxor with its fine hotels and ancient remains in an excellent state of repair. This was a festive time for many visitors. At the Valley of the Kings, reached on donkeys, a simple path led to the tomb of Tutenkhamen and once down inside we wandered through several rooms still containing the lesser artefacts of the discovery which had been made a mere dozen years earlier. Though tourists were few the swarm of local sellers of scarabs and effigies was hyperactive. We saw the New Year in amongst lively company and then returned to our overnight carriage accommodation. The next day we went by Ghary, the open four-seat horsed carriage still much in use in Cairo as here, to the great Temple complex of Karnak. The scale and magnificence of these buildings, nearly four thousand years old, is awe-inspiring. This was all too short a visit, though few wartime soldiers achieved as much during their time in the country. At Cairo station on return there were decorative red sand trails and other remnants of celebration of the return of nineteen year old King Farouk from Alexandria.

In December 1939 General Freyberg visited Egypt and agreed the suitability of Maadi for the New Zealand Division which he had been selected to command. Shortly afterwards six New Zealand Signals officers joined us in our Mess to find their feet in the country before the arrival of the main body of the troops. They added to the hilarity and enormously improved the performance of our unit cricket team. The Mess also benefited from the commissioning of a number of senior British rankers within the 7th Armoured Division, who shared our Mess. They were able, experienced, and full of good humour; a very valuable resource when a great expansion of Royal Signals was taking place. The arrival of the New Zealanders in quantity brought new experiences too. There was a rugger match between the Welch Regiment, including several internationals, and a New Zealand team. The Welch climbed the goal posts to the cross bar and tied leeks for decoration. Their opponents responded by putting one of their broad brimmed hats on the top of each post.

General Freyberg was to write later -

‘In those days, of course, Egypt was only a sideshow. There were only a few British troops there and we were offered the whole country, so to speak, for a camping ground.’

He was right about the low rating of Egypt’s priorities at that time as there was no immediate frontier being shared with an enemy country, so that the form and likelihood of any attack was uncertain.

I saw this problem myself when I was transferred to Mersa Matruh to become the Signal officer of an Infantry Brigade. It was by no means clear to me what the intended military task was. Today, with a population of 20,000, Matruh is described as ‘the principal resort on the stretch of coast known, by virtue of its mild climate, picturesque rocky coves, fascinatingly hued sea and superb beaches of fine white sand, as the Egyptian Riviera’. It is all these things but with wide open desert inland it would be easily skirted by a mobile enemy. Perhaps there were old lessons to be relearned by those who had fought in France in the previous war. With a continuous front from the sea to Switzerland there were then no open flanks.

The harbour provided a base for Cleopatra’s fleet during the conflict with Augustus. For us a Headquarters had been constructed underground, with two entrances as was proved sensible when early bombing hit and damaged one of them. Overall there must have been a misguided concept that a fortress was being built. The Signals arrangements bear this out. A complex layout of underground cables had been installed. Salts in the ground soon ate away at this intrusion and when I arrived armoured cables were being used as replacements. Throughout the system there were small inspection pits where re-routing could be arranged in the event of damage. It seems to me that this was an endeavour to reproduce on a smaller scale the system operated with skill in 1916. Was I supposed to have a lineman crouching in each of these holes ready to carry out changes ordered by me? The records, I fear, had never been maintained before my time, so such orderly restitution was never on the cards. Egyptian labourers continued to develop cable trenches, much of it through hard rock with nothing but muscle power to help them.

My operators were first class, some having served a tour on intercept work in Sarafand (now called Tsrifin). They could pick a weak signal with a wavering frequency out of the air and recognise at once the hand of any operator they knew. Some claimed that the whole process of taking intercepted messages became so ingrained that the signal flowed from receptive ear to written record without conscious intervention. Continuing our international strain a number of Rhodesians joined me. One of them, seven foot tall and handling his rifle like a toy gun, looked totally out of place plying his trade crouched over a morse key. I had an Egyptian Army counterpart named Sandîd for a while but the Egyptians were withdrawn.

Following Hitler’s sweeping success in France, the jackals were out and Mussolini brought Italy into the war on 10 June 1940. The next day we had their first deserter and shortly afterwards a captured civilian Governor and a Senior Officer picked up by the 11th Hussars started their incarceration as guests in our Officers’ Mess. Bombing started and pamphlets were scattered: -

ENGLISHMMEN EGYPTIANS AND ARABS

OF THE WESTERN DESERT!

France surrenders arms and stops fighting against the Powers of the Axis.

The hour of England and her allies as struck at last

Italy and Germany will fall on you and punish the obstinate continuators

of a ruthless struggle which shall forever mark the decline of Democratic Plutocracies. Englishmen, Egyptians and Arabs of the Western Desert,

you slave of the criminal Government of London, lay down arms ,

because we will allow no respite tho those who will resist.

This message with its several errors was repeated in Arabic on the back.

7th Armoured Division had moved into positions of readiness. Meanwhile two lessons of war were being learned. First concerned sleep. We had moved out each night to perimeter dugouts with sleeping quarters below ground and concrete cover at one end. Raid alarms were frequent and our Brigadier insisted that every time the whole group should be herded under concrete until the all clear was sounded. After a few days the loss of efficiency through lack of sleep was marked. Cover should be taken where available but takes second place where lack of sleep endangers efficiency.

The second relates to health. Operating in strange countries and climates have often resulted in casualties from unexpected illness or disease. Today these things are better understood, but dysentery and jaundice were real problems in the early days of the Desert War. Strict hygiene drills gradually reduced dysentery and jaundice was reputedly contained after examination of the way in which inoculation needles might be passing the disease from carriers to fit men. I was carried off to hospital in Alexandria with both uncomfortable complaints. Three-week attention in the Naval hospital put me right. Air raids continued in Alex though the low intensity and the small size of bombs limited the casualties. To some extent it was a show to be watched:

‘Air raid spectacle - Searchlights sweep the sky - They find - Muzzle flashes from AA guns - Bursts get closer to enemy aircraft but at the dramatic moment the target disappears round the corner of a building.’

When fit I am referred to the list of ‘benevolent women’ and by great good fortune am invited by Paul and Betty Greaves for ten days leave. Fat free diets and limitation of alcohol are not mentioned, as jaundice demanded later, and I have happy memories of a mutually enjoyable time which may be judged perhaps by the fact that I still get news of the surviving Betty nearly sixty years later.

Back at Mersa Matruh I learn that our Brigade is disbanded and that I am to return to Cairo. Perhaps our purpose had been to hold the ring whilst the fighting formations continued their training, taking the field when an attack on Egypt materialised.

The evacuation of our troops from Dunkirk ended a phase in the war, with the major operational task for the Army in Europe becoming readiness to repel invasion and preparation for an invasion of our own. This was a long-term project.

Meanwhile it was still important to carry out offensive operations wherever this was possible and it was only in the Middle East that there were land frontiers where operations were developing, thanks to the rather hesitant intervention of Italy, whose troops had advanced into the Egyptian Western Desert.

Headlines of the times talked of the successes of ‘Wavell’s Thirty Thousand’, though I am not sure of the point at which this figure applied. There is no doubt that there were great achievements by small numbers, always short of modern equipment against much more numerous opponents. The supply line through the Mediterranean had served well when the British and French fleets were in charge, but without the French contribution as Allies, the Italian fleet was the strongest in these waters. The long sea route round the Cape of Good Hope had to be used.

As well as in the desert the Italians had became active in East Africa where they saw opportunities to increase their overseas empire from Abyssinia (Ethiopia), Eritrea and Italian Somaliland. Their neighbours were British Somaliland, the Sudan and Kenya. The Italian presence on the eastern projection of Africa could become a threat both to shipping skirting Africa and to oil supplies.

Between December 1940 and Rommel’s attack on Tobruk the following May the Italians had been driven back 500 miles along the North African coast with the loss of 130,000 prisoners and the battle in East Africa had been won with Italian losses, mostly in prisoners of over 400,000. One is taught of the value of surprise in military enterprise. In this rare case it was a surprise generated by a third party, Mussolini, who set new problems for both for the British and the Germans. Perhaps we gained the most by his indiscretion. The third false step by Italy was to mount an attack on Greece, once again to the surprise of Hitler. Treaty obligations were met by Britain and a force sent from Egypt in early May. The Germans came in once again to pick up the pieces and it may have been the result of clashes of interest between Russia and Germany over Bulgaria and Rumania which led thankfully to the split up of their temporary alliance. Within three months the Germans were in charge both in Greece and Crete and the residue of our forces was back in Egypt.

In Cairo much had changed in the first year of my time in the country. Of prime importance was the development of cohesion under General Wavell and General Headquarters Middle East of Egypt, Palestine, the Sudan, Somaliland and East Africa. Not only had they been separate Commands, but also connecting communications were lacking and some of these areas reported to the Foreign or Colonial Offices rather than the War Office. The insularity of HQ British Troops Egypt before the war, none of whose units was trained or equipped for Desert Warfare, has been remarked on by Ralph Bagnold and linked with its total ignorance of Egypt beyond the Nile cultivation.

In his early time with 7th Armoured Division Bagnold had discussed some ideas with General Hobart, the foremost developer and trainer of a British armoured formation. He recommended the creation of desertworthy mechanised patrols such as had been trained in 1916. With Hobart’s full agreement, linked to his forecast of likely failure, the paper was forwarded. It was turned down. To everyone’s dismay General Hobart was replaced. General Creagh, the new Commander, was shown the note and resubmitted the paper receiving an angry reply that this was none of his business. Bagnold took the General on a three day Desert tour for him to learn something of the conditions in which he might be operating. On his return the General received a furious message from BTE asking how he had dared to leave his Headquarters. His comment was ‘How does Jumbo (Wilson) expect me to defend the frontier without having seen it?’

Months later in the summer of 1940, when Germany had cleared the British from France and the Italians had declared war, Bagnold decided that his concept was so important that he should resort to subterfuge to sell his views. The ‘usual channels’ had failed twice. He arranged with a friend who had been a Cadet with him at Woolwich and was now head of Operations to have a copy of his proposal placed on General Wavell’s desk. Bagnold was sent for within the hour. Wavell was on his own and the full discussion that took place is recorded in Bagnold’s biography. The important intelligence opportunities were rehearsed and Wavell said “What would you do if you found no enemy preparations?”. With quick thought Bagnold replied “What about piracy on the high desert?”. A grin from Wavell showed that the idea was sold. Bagnold was given six weeks to form the Long Range Desert Group, with all those concerned, including BTE, ordered to give him immediate help. Bagnold received instructions on a number of important issues and came away astounded. ‘What a man! In an instant decision he had given me absolute carte blanche to do anything I thought best.’ There were only two queries. How did Bagnold propose to get into Libya? ‘Straight through the middle of the sand sea. It’s safe because it is believed to be impassable’. The other was about climate.

In this way the Long Range Desert Group was founded with a task which was both for offensive action and as a significant provider of forward intelligence.

In the Imperial War Museum Book War Behind Enemy Lines the author, Julian Thompson, records this opinion -

‘The work done by the LRDG in their first year of existence… established them as probably one of the most cost-effective special forces in the history of warfare. Their ‘return on investment’ was consistently better, and over a longer period, than any other British special forces in the Second World War.’

The initial requirement for manpower was met largely from the New Zealanders whose progress as a Division was delayed because the ship carrying much of its weaponry had been torpedoed at sea. Responsible, self-reliant sheep farmers, accustomed to wide-open spaces would be ideal. General Freyberg was approached and permission sought from the Government of New Zealand to which he was responsible. Agreement was received to the ‘borrowing’ and a notice then called for volunteers for ‘an important but dangerous mission’. Half the Division volunteered from whom some 150 were selected.

Ralph Bagnold’s rising distinction did not stop our occasional climbing expeditions and I would be kept posted on many of his activities from time to time when we met. No doubt with careful attention to essential security I would learn of his plain clothes expedition to Turkey and his visits to Lake Chad and Fort Lami in building up arrangements with the Free French for desert co-operation. He also commended the excellent sky wave communications that the LRDG were getting over distances of a thousand miles using the simple number 11 set. Lake Chad supposedly had a population of crocodiles, though not a great risk. However with his scientists precision he did note that most of the men there were swimming on their backs.

The last and best voyage of exploration to be fitted in was late in 1940. Starting from Suez, we headed south, soon taking to desert tracks when the road ran out. The mountains inland rose to two thousand feet and storms on high ground could produce flash floods in areas of wadis, dry watercourses for most of the time. In about five miles across such an area the track had been washed right away in numerous places. A vertical drop of six feet or more could be the result, a dangerous obstacle to careless travellers. In our case earlier parties had broken down steep banks to provide reasonable slow motoring. At Ain Suchna we reached the hot springs which the Arabic name implies. The water was of pleasant and relaxing temperature, but we chose the Gulf of Suez for swimming. The beaches were covered with great varieties of seashell, coral and rock, the result of many storms in an area with few visitors to take souvenirs.

A pipeline now runs from Ain Suchna to Cairo and on to Alexandria. At that time our petrol certainly came via Suez, but not I think by pipeline. We carried fuel for our journey using the same system as Bagnold and his desert explorers had used and was still in use for the desert convoys. Square based tin containers standing two foot high contained four gallons. Each pair then had a protective wooden framework, as the tins themselves were not strong. Refuelling and cooking both relied on this arrangement. The wood provided cooking fuel and an empty tin became the stove. It would be cut to provide both air inlet and space for feeding in the wood low on one side, the top of the can being opened to allow the kettle or pot to stand safely above the fire. The system was quite satisfactory for us but the cans were not nearly robust enough for long desert journeys in army transport. Much fuel was lost and with mixed loads chocolate arrived tasting more of petrol than anything else. The German jerrycan was discovered and when production difficulties had been overcome it became the valuable container that remains to this day.

The next morning we headed south, crossing the Wadi Araba and passing el Zafarana with its lighthouse before turning inland and following a difficult track climbing 4000ft to St Paul’s Monastery in its majestic mountain setting. It and its nearby neighbour, St Antony’s, are the two oldest Coptic monasteries in Egypt.

The St Paul concerned was born in the 4th century, his tomb becoming a place of pilgrimage. In the 6th century a church was established there which had water supplied by three springs and some four acres to grow crops. In later times a camel convoy brought in some supplies every three months or so. It is astonishing that their meagre water supply has persisted to supply the foundation for some 1500 years. We were given courteous attention and shown round a place remote from the war taking place elsewhere. When invited to sign the visitor’s book I was astonished to find that the name above mine was an unknown Horsfield. Might this be a descendant of Thomas Horsfield who published a History of Sussex in 1834?

Our return journey directly to the Nile covered some 140 miles of desert driving. This journey was easily accomplished and gave me a greater appreciation of Ralph Bagnold’s journeys of thousands of miles including direct crossing of sand dunes and of a 1920s journey across the Sinai Peninsula to Petra in Jordan.

Compared with all these great events my own activities on returning to Cairo in the late summer of 1940 were rather mundane. I was to be employed as Adjutant of our widespread unit. This is an important step both in its own right and as a learning opportunity as the staff officer and executive of a unit Commander. Wartime expansion meant that my generation was gaining this education half a dozen and more years earlier than our peacetime predecessors. In early August HQ BTE, having grown out of its previous building, moved to the Semiramis Hotel, which was on a prime site overlooking the Nile. The Nile Hilton now stands there. The plan included separate offices for our new commanding officer, Lt Colonel Steward and myself, but after a few weeks more space problems required Fanny Steward to move in with me. A future Major General, he was a robust First World War soldier with an outgoing personality. His echoing laugh must have disturbed neighbouring offices. His 1916 memories of operations in Palestine included the moment when a mounted enemy officer appeared through the mist. Revolvers were drawn and six shots were fired by each party without a hit being scored before the horse was turned and the enemy cantered away. He was plainly well known and well liked as was confirmed by the number of his friends that dropped in. I would not have missed the oblique instruction and entertainment which came my way from this fine raconteur and his friends, but it did lengthen working hours.

It was odd to have a unit HQ in a major Headquarters and it meant that we were part staff officers and part regimental officers. It was eventually recognised that it was inefficient for me to live in a somewhat remote Officers’ Mess and I was placed on the lodging list and able to choose my own roost in Cairo. I found lodgings with other military on the twelfth floor of a building that housed, on the first floor, the New Zealand Club. This was just one of the many provisions General Freyberg made for the welfare and efficiency of his New Zealand troops.

It was helpful that I arrived in Egypt with the first convoy of the war and got to know and be known by many people. Cairo filled at a great pace as formations continued to arrive from Australia and South Africa, with smaller contingents from Cyprus and elsewhere. The Poles drew particular attention as they walked the streets of the city. If an officer was seen to be approaching their military protocol required that soldiers from the ranks should halt, stand to one side and salute as the officer passed. Their progress was pitifully slow.

My unit kept well ahead on variety. Large Signal Centres handling multitudes of messages and operating day and night require many men for which appropriate provision had not been made in peace. In order to meet the demand soldiers from many infantry units were drafted in. Many cap badges could be seen amongst them. It is unlikely that we were sent the best, but they buckled to and did a good job. Similarly there was an immediate need for Cipher Officers. I believe that officers of the Education Corps were trained in this skill. More were needed and officers from several Arms were drafted in, some of whom remained with Royal Signals after the war. An even greater problem arose over operators for telephone exchanges. Signals operators were taught the drills in their training but were in too much demand for working morse keys or the primitive teleprinters then in use. The problem had to be approached in a different way.

Automatic telephony was only just appearing. We had a number of main exchanges and a multitude of smaller ones. An operator was likely to be asked for a number on another exchange which, with busy operators, could be time consuming. ‘Trunk Calls’ were a greater problem as there was high demand and low circuit capacity. The exchanges were operated by night as well, though with reduced numbers. Officers’ wives played a great part in getting this system going and they and others of several nations deserve great praise.

To increase our international image we had two Palestinian Despatch Rider Sections. These were made up of Jewish individuals who had moved from their many countries of origin in anticipation of the creation of the state of Israel (which eventually happened in 1948). They brought with them little English, but many other languages. A Dutchman and a Swiss were helpful, particularly the former. ‘Orderly Room’, the procedure for Commanding Officer’s legal or other enquiries, was carried out in many languages, Yiddish being a common one. At one time we counted that we were employing fourteen Nations, including one Chaldean from Ur.

One day in November I was brought an application for a telephone job from Phyllis Horsfield, a cousin I knew well, so we got in touch. She was a great friend of our family and often joined our holidays at home or abroad. From the younger end of my father’s generation she was half a generation older than me. She had been staying with brothers in India when war was declared and started her way home, only to get stuck in Egypt. She became an Air Force cipher officer and moved in to my Pension. She joined Tony Cazenove as the second member of my family in the area. At about this time Airgraphs came into use. Small single page forms were photographed, flown home in bulk, printed and distributed. It no longer took a matter of months between the writing and delivery of a letter.

In October my younger brother Malcolm arrived, commissioned into the Worcestershires. He had trained at the Swiss Hotel School near Lausanne and become reasonably fluent in both French and German. Getting bored waiting in the reinforcement camp in the Canal Zone for a job I suggested that his languages might be useful. I trawled him round the Intelligence branches in GHQ Middle East and he was taken on by the intercept service, moving to the Desert after training to join a forward intercept section. He had an interesting war, through the desert, Bletchley Park and then into Europe. It was nice to have seen a little of him in the short time we were both in Egypt. Though I did not know it I was soon to move. We next met five years later.

My connections with the intercept world had grown over time too. My predecessor, Peter Lonnon, worked in this field on the GHQ Intelligence Staff and Harold Winterbotham had moved into the same service. Ronald Politzer, a Cassels publisher stayed for a while in our Pension and through him I got to know a number of the expert linguists plying their skills in Heliopolis. Cherrie Whitby and Pam Taylor became firm friends, with Ronnie Ballantine, an Airways pilot, joining in when available. His regular trips to and from Asmara brought back many items of good value from the disturbed market of the war there. Malcolm attended the wedding of Cherrie and Ronnie after I had left the country. A shared sense of humour was the most important characteristic of the group. It still is.

My uprooting from Egypt was as abrupt as my departure from England had been. General Penney, the Signal Officer in Chief, inspected our unit on 6 January 1942. When he discovered what I did as Company 2nd in command, he remarked to the poor newly-arrived Company Commander “What the hell do you do?” He went on to say that his Corps could not afford the luxury of such appointments at Company level. Four days later I was posted to Singapore and within the next fortnight my journey started. Preparations and farewells were rushed.