Chapter 25: Cambridge - Clare College

Driving north towards the city of Cambridge, the bronzed autumn leaves signalled an English autumn. I was twenty-one when last I saw such a scene and this was a decade later. Everything in my world was good and the future had much to offer. Then, within days of my arrival, a telegram and then a telephone call told me that Malcolm was at death’s door. On a foggy evening on the Isle of Wight he was returning home on his ancient motorcycle. Striking a grassy bank he was thrown so that his head struck a signpost. This was before the age of the crash helmet that would have saved him. He survived but a few days. He had been the herald of happiness and new times when born in 1920 after the setbacks of my parents in the 1914 war years and now he was gone. One friend wrote to me of the ‘David and Jonathan’ link between Malcolm and myself. We had never learned that this closeness was unusual in families and very special. The Oundle School Laxtonian magazine published an In Memoriam by a contemporary that said:

‘I do not remember anybody disliking him even for a single minute throughout his entire stay at Oundle Those who knew him have a vivid memory of a strong and happy personality.’

It was a relief to me to be surrounded at Cambridge by my friends from Ripon. We had been scattered to different Colleges in the University, so I became familiar with several beyond my own, particularly Corpus, Johns and Trinity, the latter favoured by my family in the two previous generations. I had been on the books of Clare since 1939 through Harold Taylor my skiing friend. Harold’s talents had been well tested since becoming a Wrangler, working first under Lord Rutherford, another New Zealander, in the Cavendish Laboratory. Having continued a Territorial Army connection started in New Zealand he was soldiering again on the outbreak of war. He became Senior Instructor in Gunnery at Larkhill. He was the first non-regular officer to receive the Lefroy Gold Medal for furthering the science and application of artillery. In 1945 the Vice-Chancellor asked for Harold’s return to Cambridge where he became University Treasurer.

No one will dispute the statement that Clare is a beautiful College. Founded in 1326 its mediaeval buildings suffered fire and decay with the advantageous result that the site was cleared three hundred years later and an architectural gem constructed. It is said to have the air of a Renaissance palace. Standing next to King’s College, each serves to show off the other. In 1650 sanitary arrangements were primitive and even with improvement remained so. In snow, frost or moonshine the lightly clad inhabitants of the various ‘staircases’ could be seen proceeding across the courtyard to their ablutions with sponge bag or other requirements. I was allotted rooms in the new buildings of Clare, approached across the river Cam by the oldest bridge in Cambridge and woodland pathway to the ‘Backs’. In a 1930 building, my room was comfortable and convenient.

Our evening meals were taken in the fine hall with ceremonial grace on the arrival of the High Table members of College. As far as I was concerned this was where one got to know other members of College, though seating gradually stabilized so that one’s companions remained the same. Rationing affected the menu and whale sometimes appeared. My main reason for supporting the preservation of the species was to avoid having it on my plate again.

Officers from the RMA Woolwich were excused the first year of the degree course, though we took in an extra term of six weeks duration during the long summer vacation. The prescribed course was called Mechanical Sciences, so contained much that was not appropriate to Royal Signals. It was suggested that after success in the degree course we should stay for an Electrical Part 2 year that focussed more clearly on our needs. Looking back our difficulty is more easily perceived. The words transistor and electronics had yet to be coined and the computer was known to be a room-filling device using untold numbers of wireless valves. It would be another dozen years before computer training started in the Army and, in a dozen later still, we had satellite communications. A further difficulty for adjustment arose from the experience of nine years of practical application, often under pressure and now the basis of our learning was theory.

We were surrounded by those leaving the wartime Armed Forces who were attending University before starting on new careers. A select group of them had chosen a 15th century galleried inn as their lunching place. They called themselves the Felt Takers. They were exchanging their Services headdress for the Bowler Hat. A few of our group became Hon Felt Takers for the duration. Life was good and much was going on so education in its broader sense was going well.

Ralph Bagnold wrote of Cambridge experience starting in 1919 that he worked reasonably hard, but this was not the only priority. He would acquire a wide outlook and recover some of the missing years of youth. To me this points up the differences of out two wars. The grinding pressures and horrors of trench warfare in France over many years robbed many survivors of their youth. There were stern challenges in the 1940s, but much more effort went into training both of the individual and the formations in which they served. Whatever the pressures, our conditions were better than theirs.

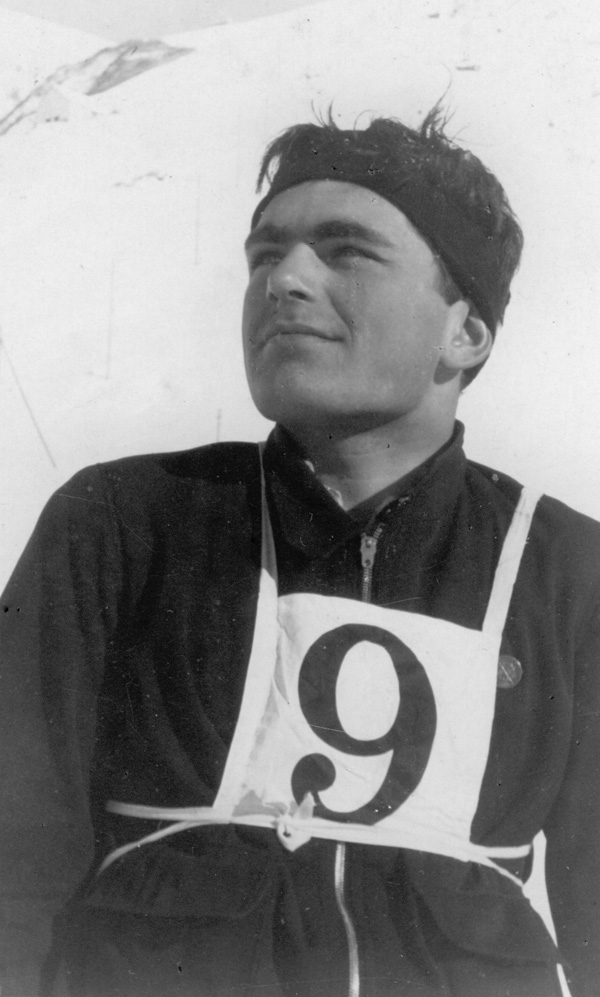

It was not long before the skiing fraternity got together as the Christmas vacation was traditionally the time for the Oxford-Cambridge races and for the British Universities team to take on the Swiss Universities in St Moritz. Financial restrictions on money taken abroad might prevent both events. However 1948 was an Olympic year and this saved us. The Ski Club of Great Britain told us that we would be included in a group of British racers who would be allowed to train in Switzerland. Each of us would be allowed to take five Swiss francs a day for personal expenses. The value of this sum was illustrated on arrival in Scheidegg. The best dressed member of our group had a suit pressed on arrival. This consumed his allowance for the day.

All travel was by train and our University group moved round more than most. Baron Franchetti wrote from Italy. He had been educated to Oxford and invited us to stay in Cortina for our own races and a further race against the Ski Club 18, a team of similar status that included his two sons. Both the Swiss and the Italians we met were delighted to welcome us back after the misery of the war years and we were not averse to staying in top class hotels with no bills to pay. Returning to the Oberland we took part in the final British Team selection race. Two of us gained places high enough for the Team but were not picked as we had missed most of the qualifying races.

However I began to be recognized in the skiing world. I was invited to join the Committee of the Ski Club of Great Britain and became Secretary of the British Universities Ski Club.

Mention can justifiably be made of a family contribution to women’s education connected with Cambridge University. My father’s maternal grandmother was a Garrett and the family had great pride in the achievements of two sisters of this family in the 19th Century. The first, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, is widely known as the first English female doctor to qualify in England. The younger, Dame Millicent Garrett Fawcett, was no less distinguished as her title indicates. Her husband and daughter have a part in the Cambridge story too.

Elizabeth qualified as a medical practitioner in 1865 shortly before her 30th birthday. She practised as Mrs Garrett Anderson M.D., rather than as Dr Anderson. She was also keenly interested in improving the opportunities for women to get a sound education. Emily Davies, the founder of Girton College, was a close friend and it was in the Girton enterprise that ‘E.G.A.’ made her contribution to the University. A friend of mine who knew her in Penge late in her life told me of her abbreviated title. She became Mayor of Aldburgh, the first Lady Mayor recorded.

Millicent was eleven years younger than her sister. She was equally interested in women’s education but extended her efforts into suffrage, getting the vote for women in elections. She was a suffragist and not a suffragette, and it was the latter that chained themselves to lampposts and caused disruption in many ways. They got the publicity. Millicent became the President of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. The battle for the vote was long and drawn out with Royal assent on 6 February 1918. As part of their celebration Sir Hubert Parry was approached and asked to compose music for Blake’s Jerusalem. Remember the gallant ladies of the struggle for the vote when you hear this choral work.

In 1857 Millicent, aged twenty, married Henry Fawcett who was fourteen years her senior. He had been 7th Wrangler at Cambridge in the Mathematics Tripos, which I take to mean that he was the seventh in order of those obtaining 1st Class Honours. He became a Fellow of his College. Two years later he was blinded in a shooting accident. Nevertheless he was elected for the chair of Political Economy at Cambridge, became Member of Parliament for Brighton and in due course Postmaster General. His initiatives included Parcel Post, Postal Orders and sixpenny telegrams. He also introduced those little devices that tell us to this day the time of the next collection at every letter box. As a further contribution to society he was a strong advocate of the employment of women.

The tale of this extraordinary family does not end there. His daughter Philippa also read Mathematics at Cambridge, although there was still no machinery for awarding degrees to women. The results for men were read out and the male Senior Wrangler named. Next came the results for women. Phillipa headed the list with the additional information that she had gained 400 more marks than had the senior wrangler. She joined the resident staff of Newnham College.